Oxidation of Borneol to Camphor

13 Mar 2015I was not going to bother posting this up, as it lacks in pretty pictures, but ah well. Ended up publishing it on one of the forums and figured it was worth hosting here… I decided to be a bit more “descriptive” to make up for the lack of pictures!

Part 1: Oxidation of Borneol to Camphor.

Oxidation reactions are useful mechanisms for converting one functional group in an organic compound to another. Notably, the conversion of 1* alcohols to aldehydes or acids, and conversion of 2* alcohols to ketones.

You can also do things like oxidize an amine to a nitro group (I was never able to confirm this, as back then I did not have a FTIR at my disposal, but I believe it worked, your mileage may vary - some experimental procedures use this route), and the likes.

Oxidation occurs when protons (Hydrogen) is stripped away from a compound, often replacing it with oxygen. Hence oxidation. We use an oxidizing agent to perform this.

In this experiment, we use H2SO4/Na2Cr2O7 as our oxidizing agent, to convert Borneol (a secondary alcohol) to Camphor (a ketone). This is a strong oxidizing agent, and also a suspected carcinogen, so it must be handled with care. Spills of such material are a serious hazard [1].

Experimental/Cooking (Jesse! We need to cook!):

-

2 grams of sodium dichromate were dissolved in 8ml distilled water, and slowly ~1.6ml of concentrated sulphuric acid was added. I may have used a slight excess of acid due to being distracted. This was left in the ice bath to cool.

-

0.9870 grams of borneol was weighed out carefully on an analytical balance. It should have been a gram, but I was in a hurry as there were only 4 balances, and 17 people vying for them, so I was urged to “hurry the hell up”. This was dissolved in 5ml of diethylether in a 25ml erlenmeyer flask, and stirred. You would not believe how much of a pain in the arse it is to dissolve such a tiny amount of stuff in a tiny bloody container. The instructions called for 4ml of the ether, but an extra 1ml was used to wash borneol stuck to sides of it in. This was left in the ice bath to cool. At this point, a few sachets of salt were added to the ice to help with cooling.

-

Over the course of approximately 10 minutes, 6ml of the oxidizing solution was added to the borneol/ether solution with stirring and cooling to keep it chilled. After the addition was completed, further stirring/swirling/swearing was done for about 5 minutes.

-

The mixture was put into a seperatory funnel of capacity 150ml, with the flask rinsed a few times with small amounts of ether and water to get all of the material into the seperatory funnel. Some more water (10ml or so) was added to the seperatory funnel. This was done very carefully, again, see [1] for why. The seperatory funnel was vigorously shaken with repeated venting to prevent it exploding from pressure (having seen this happen before), and left on a retort stand to settle.

-

Once settled, the lower aqueous layer was drained off into one container. The ether layer was then transferred to a small beaker.

-

The aqueous layer was put back into the sep. funnel, some more ether added (around 15ml), and again shaken, swirled, vented, and let settle. The ether layer was combined with the other ether layer in the small beaker. This was repeated again (aqueous layer returned and separated, keeping ether layers together) a total of 4 times. Instructions specified 2, but I was unhappy with the “colour” of the layers. This is hard to explain, but it “seemed right” based on experience separating/extracting mixtures.

-

The combined ether layers were put into the seperatory funnel (a fair bit of the ether had evaporated over time, reducing its volume a bit), and it was washed first with 20ml of water, twice with 20ml of 5% bicarb, and again twice with water. Each time, the ether layer was returned to the funnel, with “a bit” (2 pasteur pipette loads) of ether added each time.

-

The ether layer was placed into a clean, dry erlenmeyer flask, and a lot of magnesium sulphate added (heaped spatula loads), until it no longer formed clumps with considerable stirring, but remained as a powder. The MgSO4 was anhydrous/dry, and was there to absorb the water. It forms clumps with water, hence when no more clumps formed, it was considered dry.

-

The ether layer was filtered out and retained, the residue discarded. The ether layer was placed in a small evaporating dish and heated on a steam bath until the ether evaporated. This was a visually impressive spectacle (probably amplified by a nonfunctioning fumehood leading to inhalation of fumes…), with it “bubbling up” and forming “powder bubbles” as the last of the ether evaporated.

-

The crude camphor was then weighed.

-

Using a sublimation apparatus (which looks suspiciously like a piece of drug paphernalia), the camphor was purified by subliming/recrystallizing it. This was also incredibly visually impressive, the initial evaporation and condensation looked somewhat akin to the process that occurs in an incredibly well cooled waterpipe.

-

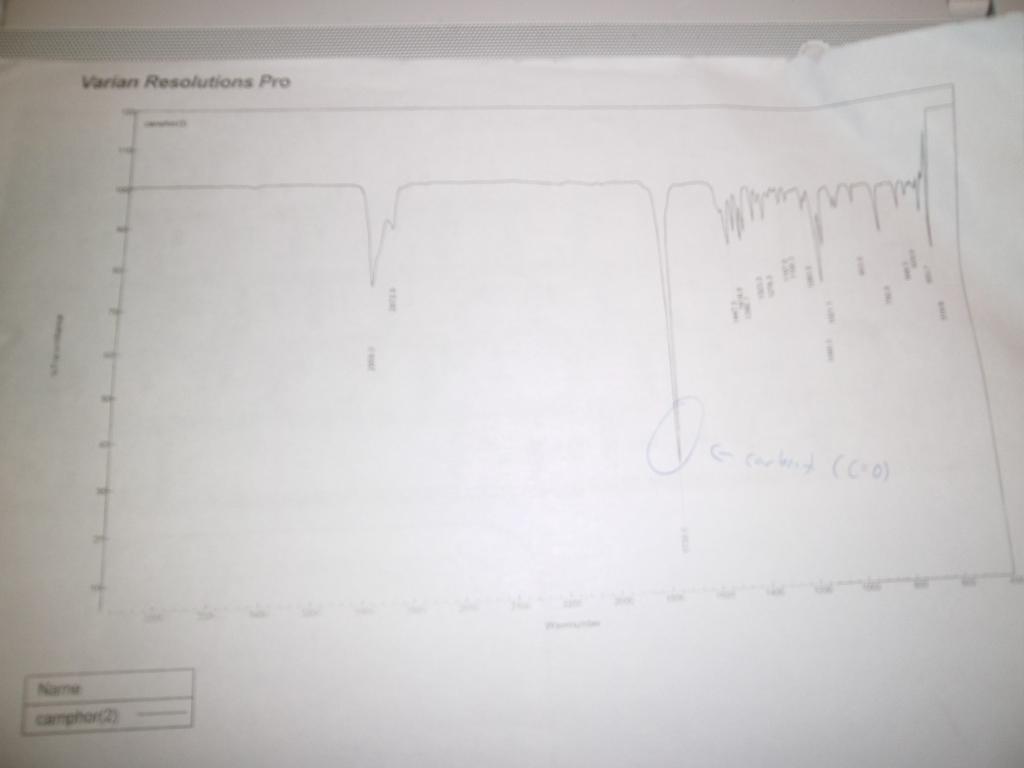

The sublimed/purified camphor was then weighed and analysed using the FT-IR machine, which, because the computer attached to it runs Windows XP Service Pack 1, took a few attempts to get it to “just bloody work” and give me a graph. The graph is attached as a photograph, lightly annotated (the C=O peak highlighted).

Results:

Mass Borneol Used: 0.9870g

Theoretical Yield: 0.9805g

Mass Camphor (Crude): 0.5281g

Mass Camphor (Pure?): 0.4454g

Actual Yield (Crude): 53.51%

Actual Yield (Pure?): 45.13%

Mm Borneol: 154.25g/mol

Mm Camphor: 153.23g/mol

Reference/Notes/Silly things:

[1] The guy working beside me did not exercise due care while putting the reaction mixture into a seperatory funnel, forgetting to check was the bloody valve closed. As expected, the reaction mixture went absolutely fucking everywhere, making a strange “bubbling” as it hit the table (a plastic coating on the table I think?). The lab techs reacted in a fashion I would expect if he spilled pure bloody cyanide everywhere, decontaminating it with bicarb and such

Also, amusingly, the table is still stained despite repeated washings with bicarb, acetone, and water. Brown “burns” on the surface, which I suspect were caused by it being oxidized.